Hierarchical and networked data appears everywhere in modern databases: organisational charts, product category trees, dependency graphs, and even transport networks. Applications need to retrieve this data to draw a chart, find out whom a certain employee reports to, or find the routes that connect two train stops.

Storing and querying this kind of data in a relational database is not trivial. If it’s modelled poorly, you might easily end up running a query for each node: an example of the infamous N+1 issue that doesn’t scale, and usually represents a performance bottleneck. This article shows you how to design tables to store tree or graph data, and how to navigate these structures efficiently with a single SQL query.

We’ll use example written for MariaDB, but the SELECT queries work equally well with PostgreSQL.

Querying Trees

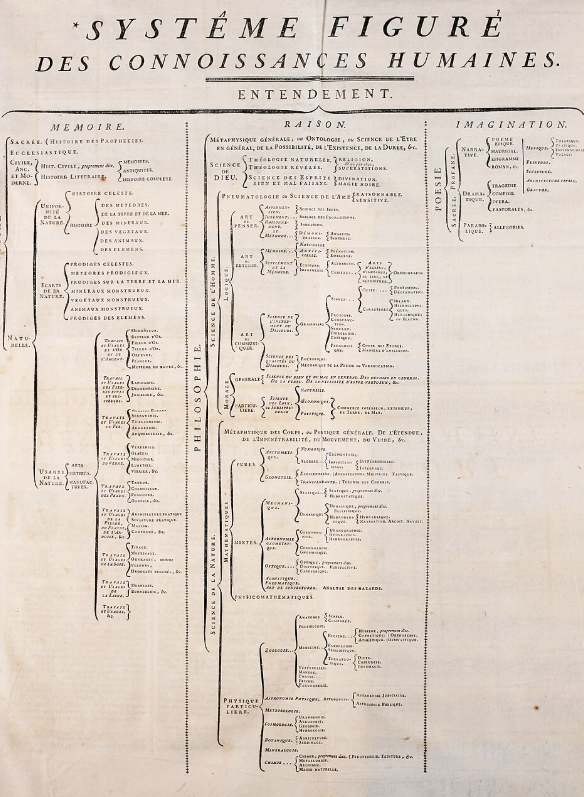

A tree is a data structure where nodes have exactly one parent node, except root nodes, which have none. A node can have any number of children. Here’s an example from the Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (1752), source: Wikipedia.

Variants

There are variants. For example, you might require that a node has exactly 0 or 2 children. You can still use the above table, but you’ll have to enforce this constraint on the application level, which requires additional queries. Or you can enforce it with stored procedures to add 2 children and delete 2 children, and make sure that the application user doesn’t have permissions to directly write to the table. But, in this case, it might be easier to invert the relationship’s direction: you can remove parent_id, and add child1 and child2 columns.

We can’t cover all variants of a tree in this article. By reading the rest of the text you’ll find out the principles, and you’ll have to figure out by yourself how to apply them to any variant you might need to implement.

Tree Tables

Let’s see how to represent a tree in a database with an example. The following table represents product categories, where a category can contain other categories. You can create the following table with MariaDB:

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE category (

id INT UNSIGNED AUTO_INCREMENT,

parent_id INT UNSIGNED,

name VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL

CHECK (name > ''),

PRIMARY KEY (id),

UNIQUE unq_id_parent_id (id, parent_id),

FOREIGN KEY fk_parent_id_to_id (parent_id)

REFERENCES category (id)

ON DELETE CASCADE

ON UPDATE RESTRICT,

UNIQUE unq_name (name)

);The key parts are:

id: Normally I recommend to use theUUIDdata type for primary keys, but we’re going to useINTto make the results more reasable.parent_id: For root nodes it’sNULL, for other nodes it points toid. This allows self-joins or, in simple words, connecting a row from this table to another row in the same table.- A foreign key called

fk_parent_id_to_idofficialises this relationship.

Step-By-Step Operations

Let’s start easy. The following are simple queries that can be used to navigate the tree step by step, using the id and parent_id fields. Let’s assume that we are navigating statrting from the row with id=11.

Find the immediate parent

SELECT id, parent_id, name FROM category WHERE id =

(SELECT parent_id FROM category WHERE id = 11);Find the immediate children

SELECT id, parent_id, name FROM category WHERE parent_id = 11;Find all siblings

SELECT id, parent_id, name FROM category WHERE parent_id =

(SELECT parent_id FROM category WHERE id = 11);Find next sibling

SELECT id, parent_id, name FROM category

WHERE

parent_id =

(SELECT parent_id FROM category WHERE id = 11)

AND id > 11

ORDER BY id

LIMIT 1

;Find previous sibling

SELECT id, parent_id, name FROM category

WHERE

parent_id =

(SELECT parent_id FROM category WHERE id = 11)

AND id < 11

ORDER BY id DESC

LIMIT 1

;Obtaining a Tree From a Query

The following query returns trees starting from root nodes:

WITH RECURSIVE category_tree AS (

SELECT

id, parent_id, name,

id AS root_id, 1 AS level, TRUE AS is_root

FROM category

WHERE parent_id IS NULL

UNION ALL

SELECT

c.id, c.parent_id, c.name,

ct.root_id, ct.level + 1, FALSE AS is_root

FROM category c

INNER JOIN category_tree ct

ON c.parent_id = ct.id

)

SELECT id, parent_id, root_id, level, is_root, name

FROM category_tree

ORDER BY root_id, level, id

;

+------+-----------+---------+-------+---------+------------------+

| id | parent_id | root_id | level | is_root | name |

+------+-----------+---------+-------+---------+------------------+

| 1 | NULL | 1 | 1 | 1 | Home & Garden |

| 11 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | Kitchen |

| 12 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | Bedroom |

| 111 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 0 | Ovens |

| 112 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 0 | Cookers |

| 113 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 0 | Fridges |

| 121 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 0 | Beds |

| 122 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 0 | Wardrobes |

| 123 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 0 | Night Tables |

| 2 | NULL | 2 | 1 | 1 | Electronics |

| 21 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Computers |

| 22 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Audio & Video |

| 211 | 21 | 2 | 3 | 0 | Laptops |

| 212 | 21 | 2 | 3 | 0 | Gaming Computers |

| 221 | 22 | 2 | 3 | 0 | TV |

| 222 | 22 | 2 | 3 | 0 | Wi-Fi |

+------+-----------+---------+-------+---------+------------------+Le’ts analyse this query.

We have a recursive Common Table Expression (CTE) called category_tree.

The CTE starts with an anchor part, which obtains the root nodes and runs only once:

SELECT

id, parent_id, name,

id AS root_id, 1 AS level, TRUE AS is_root

FROM category

WHERE parent_id IS NULLThen we have an INNER JOIN that recursively joins the CTE’s results with the category table:

SELECT

c.id, c.parent_id, c.name,

ct.root_id, ct.level + 1, FALSE AS is_root

FROM category c

INNER JOIN category_tree ct

ON c.parent_id = ct.idThe first time, it will only joins the root nodes (the anchor part’s results) with their immediate children. Then, it will join these two levels with their immediate childre. And so on.

The anchor part and the recursive part are merged using UNION ALL. The reason is that there can’t be any duplicate rows, so there is no need to do any additional work to remove them.

Finally, we have an outer query that orders and returns all the results from the CTE’s last execution.

Note that we have some additional columns. They aren’t required, but you might find the, useful in some cases. These columns are:

root_idis the root node’s id. It’s useful if the root level is particularly important for you.root_idis assigned in the anchor, and is copied as-is in the next levels.levelis the row’s tree level. It starts as 1 in the anchor, and is incremented at every CTE execution.is_rootisn’t necessary in this case, because you might check whetherparent_idisNULL. But a root node returned by your query might be any node at any tree level. For example, you might arbitrarily decide that it’s the node withid=12. In this case,is_rootmight be useful. t’s assigned toTRUEin the anchor and toFALSEfor the next level.

Querying Graphs

Graphs can be considered similar to trees. If you see it in this way, the main difference is that nodes can have more than one parent.

But actually, in most graphs it doesn’t make sense to distinguish between parents and children, or talk about siblings. There are only peer nodes, and links between them called arcs. These links have a direction.

In the following examples, however, we’ll use a graph that is actually a small variation of the category tree we used earlier. Is a graph, and no a tree, because a category can have multiple parents: trees don’t allow this.

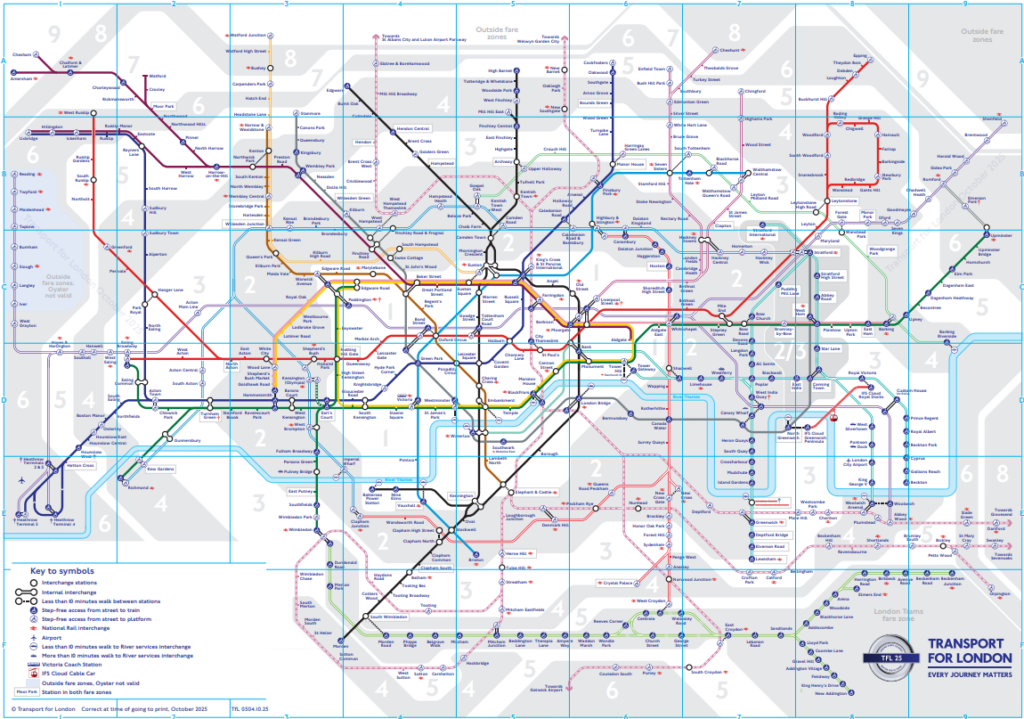

A graph example is a public transport map:

Variations

An arc may carry additional metadata, such as creation and deletion timestamps, tags, or the reason why the arc exists.

Additionally, arcs might have a weight. If the graph represents a transport map, the weight is probably the dinstance that separates the nodes linked by an arc. This might be taken into account when we need to find the shortest path between two nodes. But this is beyond the scope of this article. If you need to use weights in this way, I recommend using the MariaDB OQGRAPH engine. If there is interest, it might be a good topic for a future article.

Graph Tables

A graph table is a many to many relationship between a table and itself. Let’s see a practical example:

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE category (

id INT UNSIGNED AUTO_INCREMENT,

name VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL

CHECK (name > ''),

PRIMARY KEY (id),

INDEX idx_name (name)

);

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE category_arc (

id INT UNSIGNED AUTO_INCREMENT,

from_category INT UNSIGNED NOT NULL,

to_category INT UNSIGNED NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (id),

UNIQUE unq_from_category_to_category (from_category, to_category),

FOREIGN KEY fk_from_category_to_id (from_category)

REFERENCES category (id)

ON DELETE CASCADE

ON UPDATE RESTRICT,

FOREIGN KEY fk_to_category_to_id (to_category)

REFERENCES category (id)

ON DELETE CASCADE

ON UPDATE RESTRICT

);We modified the category table by removing the parent_id column.

The many to many relationship is represented by category_arc. As anticipated, this relationship has a direction: from_category points to a parent category, and to_category points to a child category. This design allows us to have multiple children for the same parent, and multiple parents for the same child.

Step-By-Step Operations

Since arcs have a direction, we’ll need to run queries that keep into account this direction. We’ll assume that we’re statrting from the row with id=21.

Find current node’s parents and children

SELECT

c.id, c.name,

JSON_ARRAYAGG(DISTINCT c_parent.from_category ORDER BY 1) AS parents,

JSON_ARRAYAGG(DISTINCT c_child.to_category ORDER BY 1) AS children

FROM category c

INNER JOIN category_arc c_parent

ON c.id = c_parent.to_category

INNER JOIN category_arc c_child

ON c.id = c_child.from_category

WHERE c.id = 21

GROUP BY c.id, c.name

;Find all adjacent nodes (no distinction between parents and children)

SELECT

c.id, c.name

FROM (

(SELECT from_category AS id FROM category_arc WHERE to_category = 21)

UNION ALL

(SELECT to_category AS id FROM category_arc WHERE from_category = 21)

) a

INNER JOIN category c

ON a.id = c.id

;Finding All Reachable Nodes, Recursively

The following query recursively finds all nodes that are directly or indirectly linked to the starting node. It treats parents and children in the same way.

WITH RECURSIVE category_network AS (

(

SELECT

id, name,

1 AS distance

FROM category

WHERE id = 21

)

UNION ALL

(

(

SELECT

c.id, c.name,

cn.distance + 1 AS distance

FROM category_network cn

INNER JOIN category_arc ca

ON cn.id = ca.from_category

INNER JOIN category c

ON c.id = ca.to_category

WHERE c.id <> cn.id

) UNION ALL (

SELECT

c.id, c.name,

cn.distance + 1 AS distance

FROM category_network cn

INNER JOIN category_arc ca

ON cn.id = ca.to_category

INNER JOIN category c

ON c.id = ca.from_category

WHERE c.id <> cn.id

)

)

) CYCLE id RESTRICT

SELECT DISTINCT

id, name,

distance

FROM category_network

WHERE id <> 21

ORDER BY id

;Again, we start with a CTE called category_network, and the first part is the anchor. It selects the starting node, which doesn’t have to be an edge node.

The anchor is the first part of a UNION. Second part is another UNION. This is the case because, with our table design, parents and children are linked using different columns: from_category and to_category, but our query shouldn’t distinguish between parents and children.

Another way to do this would be to write ON clauses with an OR logical operator or an IN comparison operator:

ON t1.id = t2.from_category OR t1.id = t2.to_category

ON t1.id IN (t2.from_category, t2.to_category)But this wouldn’t be index-friendly. So we prefer to read parents and children in the two branches of a UNION, which should use indexes properly. If the rows returned by the UNION are not too many, this query will be fast.

Note that all UNIONs are of type UNION ALL. This is because they can’t possibly return duplicate rows, so we don’t need the database to do extra work to remove duplicates.

Then we have cycle detection syntax: CYCLE id RESTRICT. We have to do this because, in a graph, two nodes can be connected by more than one path. In this case, we’ll have an infinite loop. To avoid this, we need to use the CYCLE ... RESTRICT clause. This query was tested on MariaDB. PostgreSQL requires a slightly different syntax for cycle detection, the the logic is exactly the same.

Finally, we have an outer query that excludes the starting node (you might want to do so or not, depending on your application logic) and sorts the rows by id.

In this query, I add an additional columns: distance. You might need it or not, The logic is the same that I used for the level column of the tree query.

Conclusions

We discussed how to store tree and graph data structures in a relational database. We discussed how to run simple next-node queries, and how to run queries that return all the nodes reachable form the starting point. For graph examples, we actually used a variant of the tree table design, which is still a logical tree but allows a node to have multiple parents. In a training, I wouldn’t do such a thing. But if you managed to follow my explanation, you learnt how to handle graphs the harder way, and shouldn’t have any problems working with a proper graph, which doesn’t have a distinction between parents and children.

We used MariaDB for the examples. Almost all the queries will work on PostgreSQL, too. But, as mentioned, MariaDB offers another interesting feature that I didn’t discuss in this article: the OQGRAPH storage engine. This engine allows us to work with weighted graphs and easily find the shortest path between two nodes. If there is interest, I can illustrate OQGRAPH in a dedicate article.

If you want to know more about trees, graphs, CTEs, or other advanced aspects of SQL, consider our SQL training courses.

Federico Razzoli

0 Comments